All throughout the month of August, we’ve been exploring nine different growing regions across China with nine different partners. With each article, we’ve been working to understand what it is about each region that makes them unique, teasing apart how regional differences influence the values of growers and craftspeople, and why our partners’ particular combination of weather, soil, varietal and craft brings them awards, national recognition and inspiring tea.

The ninth and final article in this series visits the Zhenyuan Dongsa Cooperative in the Qianjiazhai region of Mt. Ailao in Yunnan. Here in one of the original cradles of tea, this cooperative group of farmers wild-forages pu’er from some of the oldest tea trees in the world and finishes using traditional hand processing techniques.

PART NINE: Zhenyuan Dongsa Cooperative

Qianjiazhai,

Mt. Ailao, Yunnan

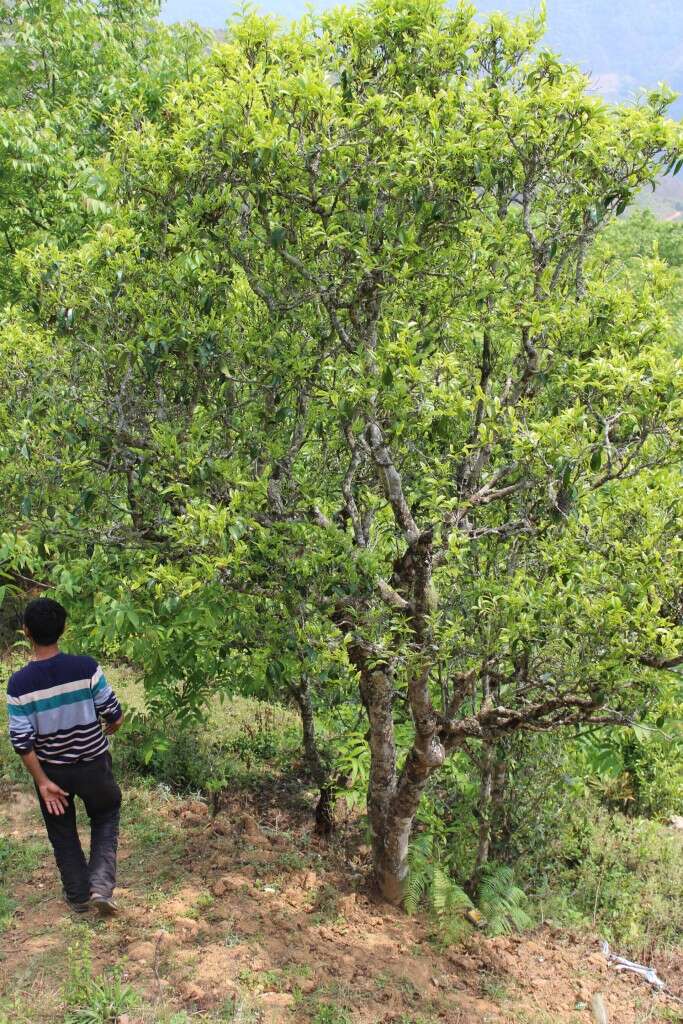

Qianjiazhai is unique among tea growing regions. Unlike most other tea regions in the world, there is a conspicuous absence of terraced mountainside fields.

Within Qianjiazhai, there is little to no cultivated tea. The members of the cooperative wild-forage from wild tea trees that have been growing for generations, scattered across the mountainsides. They have rights to sustainable foraging because they can trace back their family in the region to generations before the land was set aside as a protected forest preserve.

The lack of “cultivated” tea truly defines the region. Qianjiazhai is perhaps the most suitable natural climate in the world for tea, arguably one of the origin points for modern tea’s ancestor.

This means that there is no need for pesticides or fertilizers, and no need for trimming or watering. Most plants being picked have been growing longer than the people picking them have been alive, so they are certainly not in need of traditional care. Instead, the role of the modern tea farmer in Qianjiazhai is that of protector, watching over the land to prevent poachers from cutting down ancient trees in the middle of the night to strip their tea leaves bare for easy money.

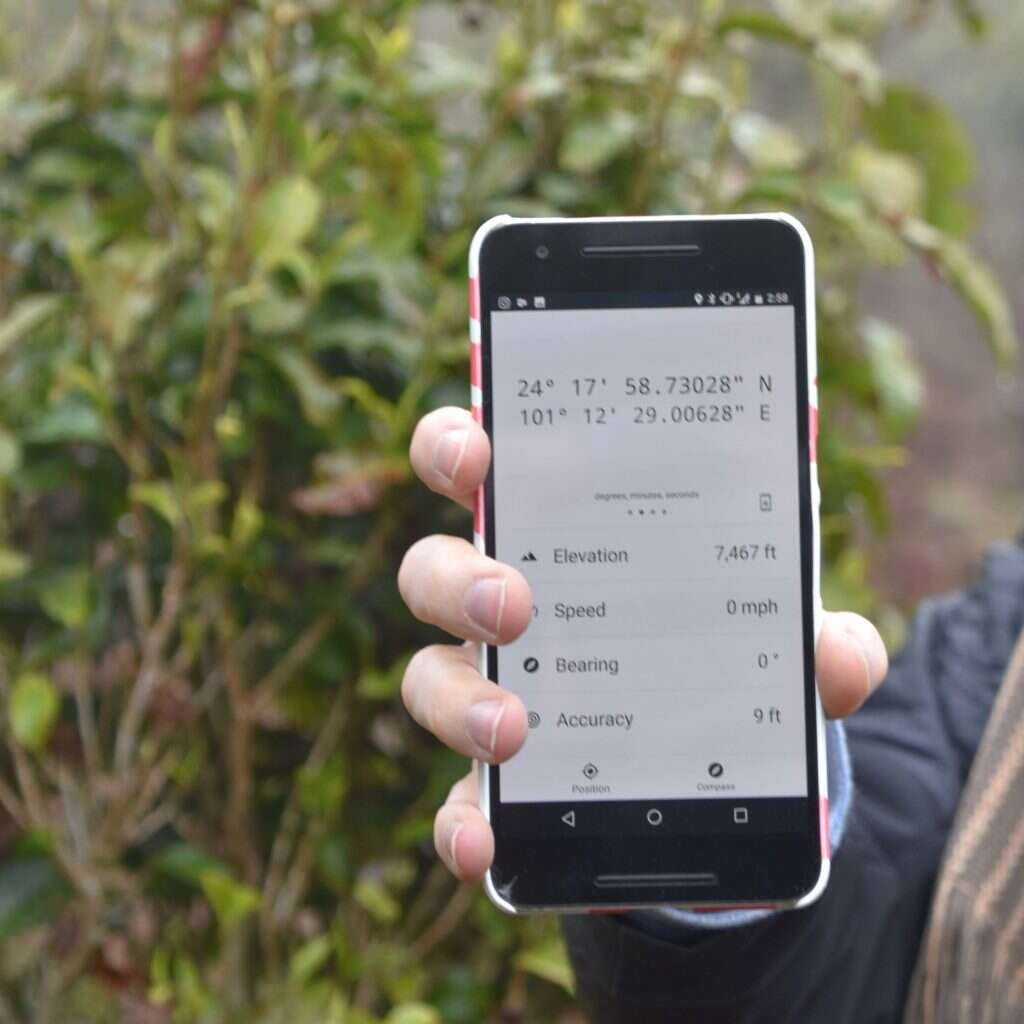

Beyond its singular wild tea forests, Qianjiazhai is defined by being one of the most remote tea growing regions in China. From the nearest airport of Kunming in Yunnan, it is fifteen hours and three transfers by bus to either Jiasa or Zhenyuan, and then another six hours to the mountain town of Jiujia. From town, it is another four to five hours in an all terrain vehicle, and eventually, walking on foot, to reach the most remote mountainsides foraged by the Dongsa Cooperative.

This intense isolation makes Qianjiazhai one of the cleanest places in China, far removed from the threat of air pollution or overdevelopment.

The remote location also makes it nearly impossible for the large tea brands and investors to come in and open large workshops or bring in mechanized equipment. The lack of big brand presence also means there is no money to push the region to consumers.

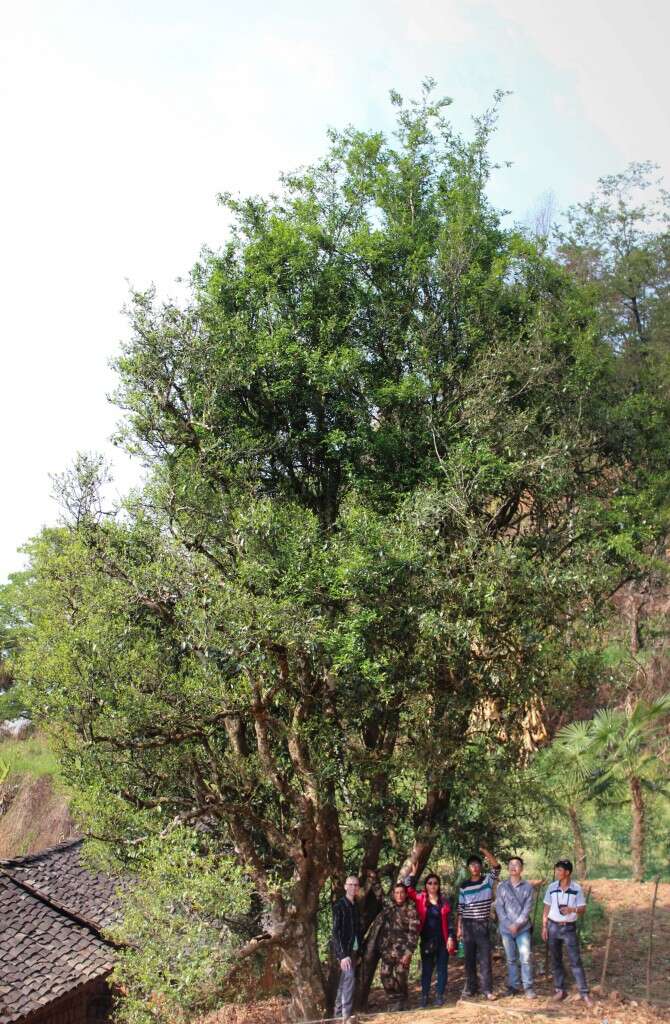

Even though its trees are older than almost anywhere else in Yunnan, regions like Jingmai and Banzhang are staggeringly more famous. The isolation means that Qianjiazhai is still small families picking by hand high in the mountains and finishing entirely by hand.

Indeed, with so many tea trees covering the mountainsides, many members of the cooperative speak about how there are far more trees to pick than there are people available to pick them.

The plentiful wild trees and the difficulty of actually selling and transporting finished tea means that there is no pressure to clear other plants or cultivate more tea. This means the whole region is still full of its natural evergreens, with hillsides covered in tulsi and ferns, scattered with tea trees between walnut trees. While many other regions are working to restore a natural balance to the ecosystem, none can boast to be as well preserved as Qianjiazhai.

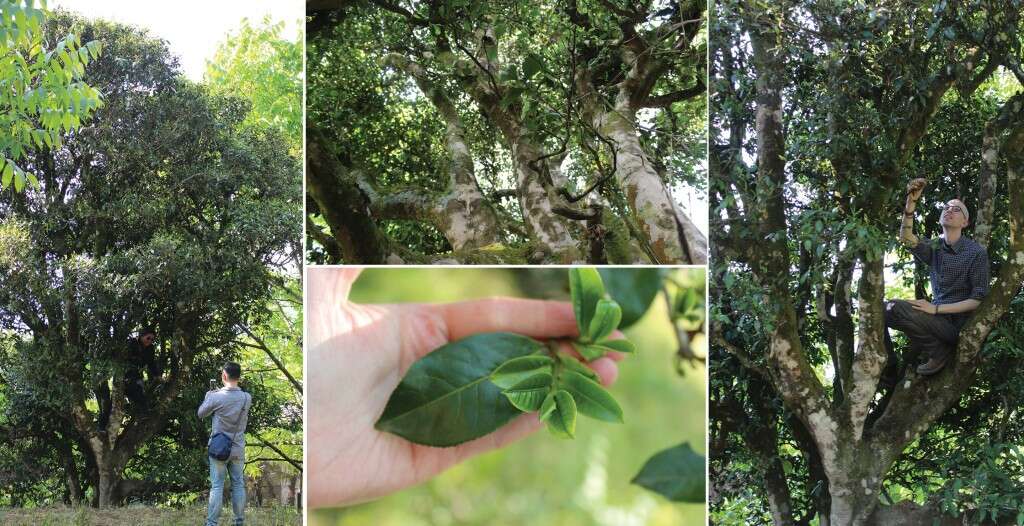

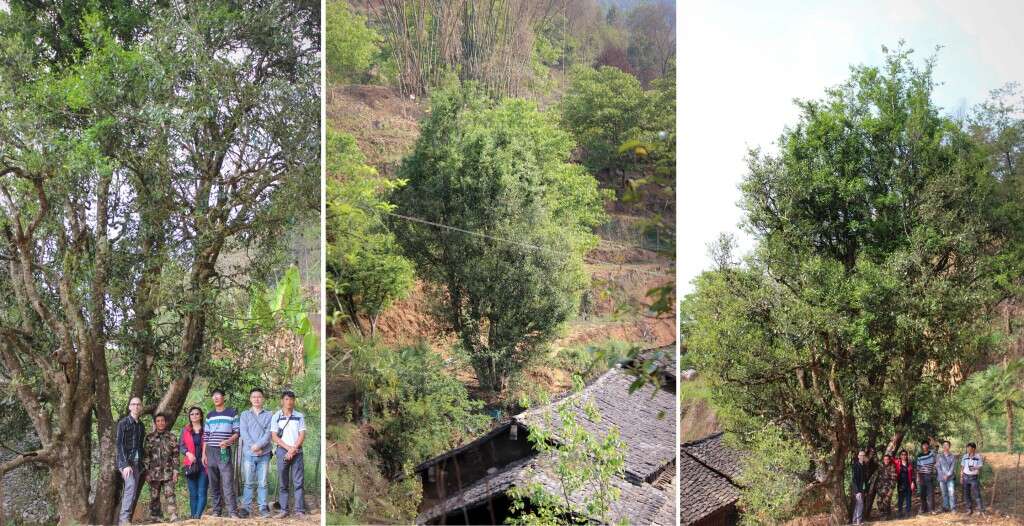

Camellia sinensis var. assamica is the most widespread, growing wild across the mountains. Some assamica stock reaches ages of well over one thousand years old, growing as twenty foot tall trees with complete canopies and thick trunks.

This is in great contrast to cultivated sinensis, which forms large shrubs or small trees more similar to lilac bushes when allowed to grow untended for generations.

Any tea the cooperative sells as sheng or shu pu’er is picked from these untended assamica trees.

The age of these trees gives them very deep roots, and the biodiversity creates an environment that stimulates the development of polyphenols and other flavor compounds as a response to challenges from other plants and insects. The rich and complex flavor of the tea of Qianjiazhai comes from these polyphenols and from the minerality taken up through the deep roots of the trees.

Because of the importance of tree age on the flavor of the finished tea, the Dongsa Cooperative separates their pickings by tree age, with Gu Hua and Gui Series pickings coming from trees between 100 and 300 years old, Zun coming from 500-800 year old trees, and for the oldest tea trees, actually separating the fresh leaves from each single tree in several kilo lots. Each tree has its own unique flavor based on how much sun it gets each day, what is growing around it, and its exact elevation.

The “Wild Tea” label is thrown around often by big workshops and brands as trendy but empty words. The Dongsa Cooperative is working to get the term “Wild Tea’ protected by the Yunnan provincial government to combat its use in low quality flatlands pu’er.

Their definition of wild tea is actually quite simple. To be labeled as wild tea, they believe that a tea plant should be able to grow without any human intervention. Any tea tree that requires watering, trimming, pesticides or fertilizers any time in its lifecycle does not qualify. To them, this is worth protecting because the quality of flavor and texture is so different with wild tea, and with bigger and bigger pollution problems closer to urban areas, true wild tea represents the cleanest and purest possible tea on the market.

Mr. Zhou is the current organizer for the cooperative.

He has spent his whole life living in Qianjiazhai, and his goal above all else is to invest in the future of the region. For him, the cooperative is only a start. The cooperative provides the framework for families living in isolation on peaks across the region to work and learn together, to grow stronger and feel hope and optimism in the future of tea craft.

But tea is not Mr. Zhou’s first calling. He dedicates most of his time to his first calling, working as a middle school teacher in his hometown of Jiujia. Middle school is the highest level of education available in the town of Jiu Jia, and together with his fellow teachers, Mr. Zhou prepares his students for higher education in Zhenyuan and beyond. He makes sure that everyone in the township has the basic tools of fluency in reading, writing and speaking Mandarin, as well as math, history and geography.

For Mr. Zhou, these are the foundation of success. The world over, farmers without the benefit of formal education will often continue the family trade because it seems like the only choice. With education, Mr. Zhou believes that people can choose to be farmers if they wish, or pursue any other career that makes them happy. The people who stay will bring energy and innovation to the area and make it better for future generations. Mr. Zhou is proud to know that many of his students over the years have gone on to study at prestigious universities across China.

Mr. Deng is an inspirational reminder of why we love tea so much, and why it is important to tell the stories of the people behind each cup we have the privilege to sip.

Mr. Deng has had to work to get to where he is today. His biggest dream as a child was to learn to read and write, to go to school, but his father couldn’t afford the cost of tuition, books and uniforms, nor did the family have a way to make the long drive to town for classes.

Mr. Deng took the initiative himself. He walked the full day’s walk to school and asked to be allowed to join the class. Though the teachers were skeptical he would be able to keep up with the other students, or even afford to keep attending school, they agreed to let him try.

On his long hikes to school, he picked walnuts all the way into town, and set up to sell the walnuts before and after school. In this way, he was able to raise enough money to stay in classes. At night between school days he slept at school, only returning home once a week.

Mr. Deng attended school formally for three years – enough to teach himself the basics of reading and writing – before he had to drop out to earn money for his ailing father. He continued picking walnuts, slowly expanding into a real business, where he negotiated rights to pick across many acres and partnered with neighbors to pick more, roast walnuts and sell them in larger towns. He used much of his income to establish a new sleep-away elementary school, providing more access to education to children across the region.

Over the years, Mr. Deng recognized that countless wild tea trees were growing alongside the walnut trees. He and his neighbors would pick and finish tea as an aside. It wasn’t until Mr. Deng met Mr. Zhou at an educational conference that he began to seriously study crafting tea. Mr. Zhou visited to teach in the a nearby town, and one day Mr. Deng served him a cup of tea. Mr. Zhou exclaimed that the quality of leaf was fantastic, even if the craftsmanship was still a bit unpolished. He encouraged Mr. Deng to devote more energy to tea and offered to teach Mr. Deng all he knew about picking, roasting and sun-drying.

Mr. Deng got in touch with old classmates and raised enough money to build his own workshop, inviting friends and neighbors from his home town to pick tea when they weren’t picking walnuts. He passes on his knowledge and offers a generous price to anyone who can help him pick tea, remembering his own hardship as he got started as a wild forager. He and his wife officially joined the Dongsa Farmer’s Cooperative five years ago, and his craftsmanship has been getting better every year while studying with Mr. Zhou and other members of the cooperative.

Mr. Deng, his wife, and his neighbors can live a much better life as tea farmers, while also acting as stewards to otherwise unregulated land. By teaming up together, they can prevent outsiders from coming in secret and picking trees irresponsibly.

They have been able to use their profits to expand the local elementary school that is easier for children to walk to from their homes, and have even dug out and built their own roads to connect remote three-to-four family settlements across the mountain that were once isolated. Mr. Deng’s optimism, self sufficient spirit and eagerness to learn are a source of hope for the whole region, and a wonderful sign for us tea lovers that the craft of tea in Qianjiazhai will continue strong for years to come.

The Li Family of the cooperative live in one of the most remote mountain townships of all, impossible to reach if not for Mr. Li’s all terrain vehicle, on loan from the local government to help him in his work as the environmental conservation officer for the Qianjiazhai region of the Mt Ailao National Forest Preserve.

His job is to make sure that neighbors or even outsiders and poachers aren’t picking from illegal-to-harvest wild Crassicolumna trees to make yabao, and to help safeguard the land for future generations.

Mr. Li’s view on conservation in such a remote region is that it only works if every farmer can be enlisted to help the cause through mutual benefit, not fear of punishment. This goal to raise up the region motivates him to teach tea crafting with Mr. Zhou, and to allow farmers to forage in small sustainable amounts from the wild old trees that are growing on their own land, as long as they don’t over-pick and help protect the trees from outside poaching.

So far these policies have helped stave off threats to the region and helped create a better future for people, including his own family, living so far from roads and cities.

Every member of the cooperative is very forthcoming about the amount of hardship they have experienced, working to carve out a living through the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution, but across each family, there is unity in the hope that the next generation – the kids growing up today – will live lives of greater comfort and reach higher levels of education than their parents before them. The cooperative is working together to raise each other up through tea.

In almost every other tea region, a huge part of the craft is field management. The decisions of when and how to trim back tea plants, where to cultivate which cultivar and how to care for each plant in the off season all go into the flavor of the tea.

In Qianjiazhai however, there is no specific craft in plant care. Farmers here are true foragers, actually climbing the taller tea trees to pick leaves. The craft of picking has most to do with knowing when exactly to pick which tree and how much stem to leaf to bud yields the richest most nuanced flavor. While much of the pu’er industry prefers just the pretty buds, Master Zhou is working to teach other farmers to pick the tender stems along with the buds where much of the sugar is stored to yield a thicker more complex texture.

After picking, the most traditional technique is to spread the leaves thin and allow them to sun dry in the brilliant Yunnan sun. On cooler or cloudy days, a light firing in a wok helps eliminate moisture more quickly. The key is not using too much heat to avoid the smokey flavor that some young sheng pu’er can have. This tea is stored loose until an order comes in for cakes, at which time Master Zhou lightly steams the finished leaves and forms them into balls by hand, or presses them into cakes using a traditional hand-carved stone mold.

Several of Master Zhou’s students have begun experimenting with the more modern shu pu’er style, allowing the tea to dry much more slowly by piling the fresh leaves and covering them to allow them to ferment very slowly. The young buds are sold as Gong Ting Shu Pu’er and the balls that clump together are sold as Lao Cha Tou (Shu Pu’er Nuggets).

Even more recently, several families have begun producing a traditional black tea in an older unique regional style. Spreading loose fresh tea in thicker layers on bamboo mats to dry in the sun slows the evaporation of moisture and gives the tea more time to oxidize, creating black tea. This tea can be finished without heat for maximum aging potential or roasted in a wok to bring out deeper dessert-like notes.

Master Zhou travels from household to household throughout the cooperative and is deeply familiar with the profile of each member’s micro-climate in Qianjiazhai. He presses cakes as single tree pressings to highlight seasonal variations on request, but is also capable of blending between tree ages and families to create a specific and consistent flavor profile.

The developing craft of tea in the remote mountain villages of Qianjiazhai is working not only to raise up the community but to put the region on the map through pure word of mouth, not expensive marketing campaigns.

Each year, more and more people fall in love with the teas of Qianjiazhai, helping give the region enough recognition to gain the protections and grants it needs from the local government to continue making fine tea for generations to come.

How To

How To Myths & Legends

Myths & Legends Travelogue

Travelogue Tasting Journal

Tasting Journal Talking Shop

Talking Shop Tea 101

Tea 101 Watch

Watch Teaware

Teaware News

News

Leave a Reply

Lovely story, very much enjoyed reading about the region, the forests, the people and the time-consuming process they go through to bring us these delicious teas :)