Sipping a cup of tea today is a connection to countless generations of tradition and thousands of years of history & folklore – from the first mythical cauldron of tea tasted by Emperor Shen Nong, to the infusion in your glass. With its origins shrouded in Taoist and Buddhist folklore, even the lightest brew is heavy with provenance. Even still, connecting back to mythical emperors and Taoist sages is a bit harder than connecting with the real people who made tea what it is today.

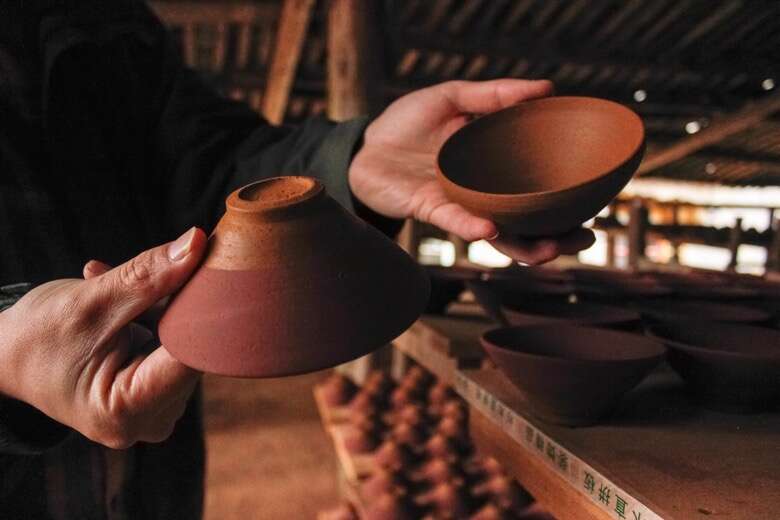

Tea was not always what it is today. Originally a precious medicinal herb, the plant finally earned its own name and became ‘tea’ under the influence of Lu Yu of the Tang Dynasty, when the idea of brewing tea without salt and other spices and herbs was introduced. Yet it was under the Song Dynasty that tea was truly born into a culture of its own. What changed? At this moment – finally! – ritual objects were made specifically for tea and for no other purpose.

Tea culture was truly born

the day that the Jian

Kilns

started firing.

The power of tea across the world comes from the ritual with which we brew and taste. We see this from the Chado of Japan and the samovars of Russia, to the porcelain and silver services of England, and of course, the gong ceremony of China. These rituals teach us to appreciate tea as more than a beverage. They teach us to slow down and appreciate tea as a part of our way of life.

Until the Jian Kilns of Shuiji started firing, tea was made in borrowed wares.

Bowls made for wine were taken out for tea tasting. Yet under the influence of the Song, (especially emperor Song Huizong who wrote an entire treatise on the subject) tea ceremony grew into an important ritual all of its own.

In the Song Dynasty, tea was pressed into ‘green tea’ cakes, similar in some ways to the sheng pu’er of today. In Wuyishan – known today for its fine roasted oolongs and black teas – much of the best green tea in the world was being picked and pressed into cakes. Tea lovers would get together in the tea villages of Wuyi like Tongmu and bring their very best teas.

The tea cakes would be ground into a fine powder using a stone mill, and that powder was whisked into a froth in bowls. The bets teas were judged by the purity and whiteness of their froth. It was in some ways similar to the latte art competitions baristas get together for in modern times.

At many of these competitions anyone was welcome to attend and cast their vote on the best tea. These competitions survive to this day, now held in outdoor tents in a public square in Wuyishan, attended by seasoned veteran tea drinkers, farmers and even tourists, who all get to weigh in on the best harvests of the year.

The appreciation of the light frothy foam on a fine bowl of tea eventually led people to contemplate the amount of work that goes into producing tea and into learning to brew and whisk it perfectly. In contract, the tea was still being served in borrowed wine bowls. It was then that the important step was made to thoughtfully contemplate and design the ideal tea bowl.

Through much trial and error, the perfect tea bowl was formulated, and it was called Jian Zhan.

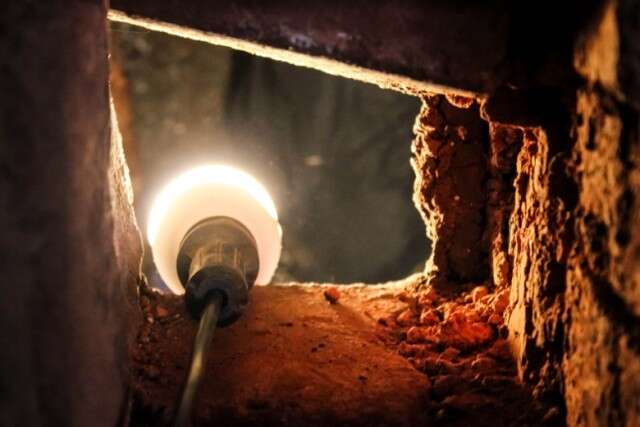

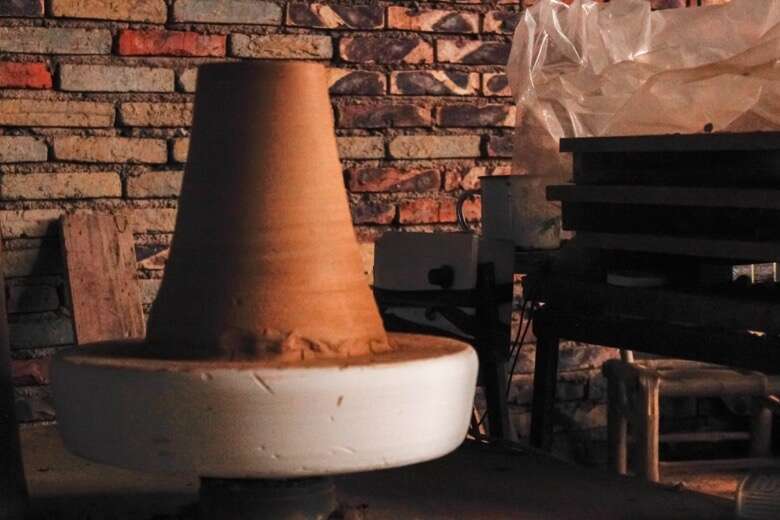

The Lao Long Kilns were built to fire Jian Zhan pieces outside of Wuyishan in a village called Shui Ji. This village was perfectly situated because it sat on top of the most perfect clay and the best minerals for glazing. Naturally iron-rich clay was dug from the ground and blended to perfect proportions, then allowed to age in troughs of water for as long as five years to achieve the perfect density before firing. Shui Ji also had access to pine forests to prove the perfect hot clean burning wood for the best temperature in the kiln.

Jian Zhan bowls were designed with the perfect shapes and angles to hold the frothy tea and accentuate the aroma of the liquid. But most importantly, they fired deep dark blacks and reds with flecks of gold. These dark colors were the perfect contrast to the white and green of the tea they held, making the tea seem even more pure. The natural firing techniques led to great variation, in line with the Song Dynasty scholarly values of appreciating the beauty of nature. With each bowl fired completely unique, the competition of tea whisking and drinking took a step towards a true tea ceremony when the beauty of the bowl encouraged contemplation while sipping.

The ceremony of whisking tea in Jian Zhan bowls is the great ancestor to both Chinese gong fu tea and Japanese Chado. Japan studied tea culture in China during this period and worked to attempt to recreate the perfect conditions of nature in Shuiji through Tenmokku ceramics, which led to the wider art of creating the perfectly imperfect chawan.

The beauty of Jian Zhan is undeniable and stunning. The pieces fired in the Song Dynasty have an incredible luster. The deep black of their glaze is flecked with gold, like a dragon’s hoard long lost to a dark ocean, or stars across the night sky. The black is broken by deep fractal-like crystalline structures that glow silver-blue, and accented by deep reds and oranges. Every piece has a different balance of these elements depending on the temperatures it was exposed to in firing within the kiln. There is no way to control for one style or another in true kiln-fired Jian Zhan. The beauty of each piece is its own by pure happenstance.

Did You Know?

Jian Zhan from the Song Dynasty has been the subject of recent study by scientists who discovered that it contains a unique and incredibly difficult to produce crystalline formation known as epsilon phase iron oxide. This formation is produced in modern labs using massive amounts of electricity in tiny quantities for use in precision data-storage electronics. The formations in Jian Zhan ceramics occurring naturally are staggeringly larger than those produced in labs. Coincidentally, the Jian Zhan pieces with the highest count of epsilon phase iron oxide are also some of the most coveted for their very beautiful silvery appearance!

One of the beautiful attributes of Jian Zhan lies in their crystalline structures. These occur in the natural glaze through firing, and these will subtly change over time through constant use. Tea oils are slowly absorbed into the cup, not so much building a patina (like yixing tea pots) as very slightly altering the way the crystals refract light, acting as a sort of ‘lens’. This effect grows through constant use of a Jian Zhan tea bowl, making it more beautiful over time.

This very subtle effect gave Jian Zhan the kind of collectible value in the Song Dynasty that Yixing teapots have today. The incredible glaze was even thought to slow the way that green tea slowly becomes flat and off if left in a cup for a long time, meaning that green tea whisked at competitions would better preserve its full, crisp sweet quality.

Tea oils are slowly

absorbed into the cup,

altering

the way the crystals

refract light.

While many specialized implements for tea ceremony would come over the next many hundred years, Jian Zhan was the first. It is still one of the most perfectly realized objects devoted to the beauty and culture of tea. How sad then that the Jurchen invasion brought the Song to an abrupt end, and with it, the secrets of Song dynasty Jian Zhan glazing and firing techniques were lost. Tea culture in China was flourishing like never before, only to suffer a great cataclysm that would change its course permanently.

In contrast, Japan continued the Song dynasty tradition, elaborating on the Song ceremony to create Chado. With their source of Jian Zhan bowls cut off, they worked to fire replicas called Tenmoku, which developed into a beautiful art of its own made to fit the very different clay, glazing, kilns and climates of Japan. Chinese tea ceremony eventually grew into the steeping of looseleaf tea with a very different set of tools developed to accentuate the beauty of full tea leaves, specifically Jingdezhen porcelain.

Up into about the 1990’s, the world believed that the techniques and quality of the Song Dynasty could never be replicated. Indeed, recreating the highly complex, chance-based firing process of Jian Zhan would be like trying to make a modern violin sound exactly like a Stradivarius down to every sound wave measured.

But things have changed. In the last thirty years, the Chinese interest in rediscovering their Song Dynasty heritage has grown. The values of the previous dynastys like the Qing and the Ming left no room for rediscovering an old heritage. The early years of the People’s Republic of China certainly left no room for looking towards the aristocratic past. The conditions for truly respecting and studying the Song have come about in China for the first time since the Jurchens captured emperor Song Huizong in 1127.

There have been many efforts to study and replicate the incredible appearance of Song dynasty Jian Zhan ceramics, but until very recently, all have come up short. Most attempts mix various clays to recreate the basic quality of the Song kiln’s naturally iron rich clay and glazes. Others use electric kilns to try to get better control and more consistent results. None have been able to create the same scale of beauty, or – on a scientific level – fire pieces with naturally occurring epsilon phase iron oxide in the same way the Song masters could. That is, until Master Xiong came along.

Master Xiong grew up in Shui Ji, and remembers when the ancient Song kilns were first excavated. Among the many shattered shards of Song Dynasty pieces in those old kiln excavation sites were true masterpieces, a remnant of Master Xiong’s heritage that can be traced back to the people who worked these old kilns.

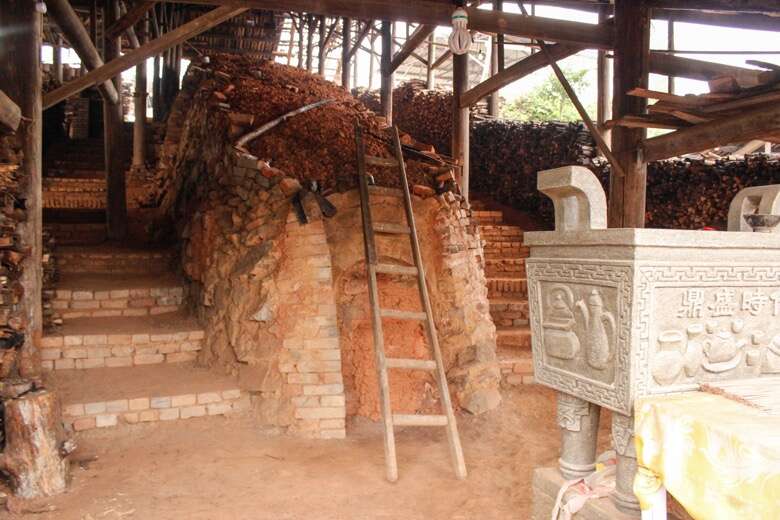

He decided to commit his life to restoring the work of the Song. While those around him studied the final pieces – the finished tea bowls produced in Jian Zhan and worked with modern techniques to recreate the same style – Master Xiong decided to take the time to work in reverse. He studied the old dragon kilns and learned how they were built, studied where the Song potters gathered material for their clay and how they fired their pieces. After years of private research, he was ready to build a revival Lao Long Kiln to the exact specifications of the Song.

Every other Fujian kiln in use before he started was government owned and run. Individual potters could rent the kiln or space in a firing for their pieces. This meant that the firing schedule was determined by market demand, and quality and frequency of firings varied depending on who was renting.

Master Xiong recognized in his research that a 300 ft long brick and mud kiln built into a mountain is a fine musical instrument that needs “tuning.” It takes a year of consistent and precise firing just to get the brick and stone and mud expanded to the right shapes and baked to the right density to conduct heat properly. Master Xiong knew that for a Song Dynasty kiln to work properly it had to run like it would in the Song, that is, as a private venture with an eye for the long term.

A 300 ft long kiln

built into a mountain is

a fine

musical instrument

that needs “tuning”

Master Xiong brought in a trusted friend and fellow admirer of Jian Zhan to back the project and undertook construction of his kiln. He chose a hill in Shui Ji with the perfect slope to recreate the Lao Long Kiln, and a place with ready access to the exact same clay used in the Song. Unlike many in Dehua, or other cities attempting Jian Zhan, Master Xiong wanted access to the exact clay and glaze materials used in the Song. Why blend to imitate when you can go straight to the source?

Master Xiong and his partner Mr. Ai worked together to build large stone troughs for aging clay. First they would dig up clay from the same earth once turned by Song potters, and fold it together into dense raw material. Then, they let the clay sit in troughs of water to slowly force all the air out of the clay. The best clay sits for years, meaning a long clay management program much like a barrel aging program for whiskey.

Meanwhile, with their kiln finished and their clay aging, they started the process of firing in the kiln: loading empty ceramic cylindrical trays to fill the space and loading in a special pine wood used in the Song Dynasty, firing once a month for a year before they were happy with the temperatures in the kiln. Finally finished with dress rehearsals, they took to crafting bowls one by one and completely by hand from their aged clay and dipping them in their carefully blended natural glazes according to strict angle and dimension guidelines modeled after the Song. They loaded their whole kiln with over five thousand pieces.

Crafting so many bowls is a full month’s work of Master Xiong and his six apprentices. Loading the bowls into the kiln takes another three to four days to make sure that balance and air flow is just perfect. Then they brick the doors to eh kiln over and cake them with mud to seal everything in and light the kiln and after burning incense and leaving offerings. Firing takes three to four days, followed by another four days for the kiln to cool.

Finally, Master Xiong

opened his kiln for the

first time.

The results were astounding.

Almost every cup

mis-fired.

At first glance, it seemed like years of construction and labor were wasted. Nevertheless, among the many pieces that Master Xiong dutifully smashed to prevent them from going to market with his name on them, there were several pieces hidden deep in the kiln that were masterpieces. They didn’t simply look like Song Dynasty Jian Zhan, they were Song Dynasty Jian Zhan. They came from the same soil, crafted with the same clay, fired in the same kind of kiln with the same wood, and with that undeniably beautiful and rare silvery markings (the kind that produces epsilon phase iron oxide).

Master Xiong and Mr. Ai were overjoyed!

Together, they spent another 15 years experimenting and continuously firing in their kiln to work towards more consistent results.

In their years of experimentation at the Ji Yu Fang Lao Long Kiln, Master Xiong and Mr. Ai have made one small but critical change to the Song process. Song Dynasty potters swished each cup in a bucket of glaze, leaving random angles of glazed and unglazed edges at the bottom foot of the cup. In contrast, Master Xiong has decided to dip straight in and out of glaze for a thicker, strong bottom that sometimes has small drip marks.

His innovation encourages deeper colors in the glaze, with more black and flecked gold. Most importantly, however, this choice distinguishes his pieces from ancient pieces.

As the first master to fire Jian Zhan pieces, Master Xiong wants to make it clear that his pieces are a continuation of the Song, not an imitation. Many before Master Xiong sought to create imitation antiques. Master Xiong takes care to make this one small but distinguishable break from the past so that his pieces can be properly identified in thousands of years.

Today, the Ji Yu Fang Lao Long Kiln is the only kiln in the world that can rightfully say that it produces Jian Zhan.

Even now, after almost twenty years of research and experimentation, there is a 90% fail rate among pieces fired in the best months. Every year, the kiln is fired once a month, with the weather lining up for one particularly exciting firing in late autumn and one in early spring. These two firings represent the most likely times of year for the conditions and temperatures to align perfectly to create the most stunning pieces (those with that epsilon-phase iron oxide!) full of silver and blue colors.

At first it is easy to wonder why so many are smashed. Many of the pieces Master Xiong destroys are beautiful in their own way. Yet a trip to the ancient kilns shows that Matser Xiong is only paying respect to his Song ancestors.

The ancient excavation sites are almost paved in the shards of broken pieces judged as unworthy by Song Dynasty potters. These potters knew that their work would outlive them, and Master Xiong knows the same. Perhaps the incredible craftsmanship of the Song comes in part from their stoic willingness to destroy anything not worthy of being passed down for generations.

Even now,

after almost 20 years of

research

& experimentation,

there is a 90% fail rate among,

even

in the best of months

You can feel Master Xiang’s excitement when he opens his kiln, the happiness in his eyes when the first pieces to come out are beautiful. You can also see the solemn look on his face when he has to pick up his special wrench and carefully shatter the pieces not worthy of being appreciated as a continuation of a thousand years of cultural heritage.

At the most promising late autumn firing, TV reporters, and enthusiastic collectors crowd around. Master Xiong doesn’t need to hire help for unloading the kiln. Collectors volunteer to roll up their sleeves and get on their knees in the ash of the hot kiln for the chance to be the first to see that one perfect piece in the firing. Everyone is giddy like children. When someone spots an incredible bowl, they grab it, cover it with their shirt and run away to examine before another collector can snatch it out of their hands. Despite the fierce competition, everyone present at the kiln opening is like a big family, united by their love for the Song Dynasty and the optimism in a future where that heritage is reclaimed.

Master Xiong and Mr. Ai have succeeded in establishing the first kiln in almost 1000 years to recreate the very first ceramics ever devoted to the ceremony of tea.

Their project of passion is possible because of their dedication and their knowledge that they are working, not for themselves, but to take a tenuous and nearly severed thread of our common cultural heritage and strengthen it.

To witness the opening of the new Lao Long kiln in Shuiji is exhilarating – to see the labor and devotion of modern humans take something sacred and revered from the past and to better than cherish it… they have brought it back to life!

Jian Zhan fires again as it did in the Song. The soil again undergoes the alchemy of fire and becomes an object in which we can see the universe. Master Xiong gives us a link to our common heritage as people, and is not content to stop. He strives to continue to improve the art as the masters of the Song before him did with each generation.

How To

How To Myths & Legends

Myths & Legends Travelogue

Travelogue Tasting Journal

Tasting Journal Talking Shop

Talking Shop Tea 101

Tea 101 Watch

Watch Teaware

Teaware News

News

Leave a Reply

Enjoyed reading this article very much. Very uplifting to Learn about the efforts of Master Xiong to preserve the Jian heritage

Great article. I appreciate the Jian Zhan history lesson!

Nice! Happy to hear that there are people wanting to preserve and improve traditions like Master Xiong. Also, I love learning more about tea history!