Kickstart your tea discovery with a free tea sampler!

Just sign up for our daily deal newsletter and we'll send you a special coupon

Have you ever wondered what makes a tea “real tea” and not a tisane?

Most people agree the difference between herbal tea and tea is simple: tea is made from Camellia sinensis, and a tisane is made from any other plant. But the truth is more complex than this. In many ways, the way we use the word “tea” in English is just as fluid as the original word 茶 (chá) we borrowed from the Chinese language.

Originally, there was no distinction between tea and any other herb. Chinese used the same word 荼 (tú) to refer to all brewed herbs. Notice how similar this is to the new word 茶 (chá) that now refers specifically to tea.

English is similar. In casual conversation, the word “tea” can broadly refer to any brewed infusion, or it can specifically refer to the tea plant (Camellia sinensis) and its leaves and brew. Though the word “tisane” originally referred to any brewed medicinal beverage, it was only recently reintroduced in English as a way to distinguish “non-tea” from tea.

In this article, we’ll explore the idea of tea vs tisane, and dig deeper to see how these definitions are being challenged by exciting herbs finished using tea craft.

What is Tisane? Is It Tea?

The word tea has a curious double-meaning in English: when you are talking about brewed beverages, “tea” can be an infusion of Camellia sinensis or any herb, spice, flower, or fruit. When you are talking about dried leaves, “tea” usually refers to the plant only, while our “tisane” definition includes all other dried plants.

Why do some people feel that it is important to distinguish between tea and everything else? Tradition is a big part of it. The tea plant Camellia sinensis - the stuff that makes black tea, green tea etc - has deep historical and cultural significance that warrants distinction.

What are the main differences between teas and tisanes?

wild-foraged Jujube leaves in Laoshan

-

• Tea comes from the Camellia sinensis plant, while a tisane can be made from any other plant or blend

-

• Tea is always caffeinated, while a tisane may or may not be caffeinated depending on the plants used

-

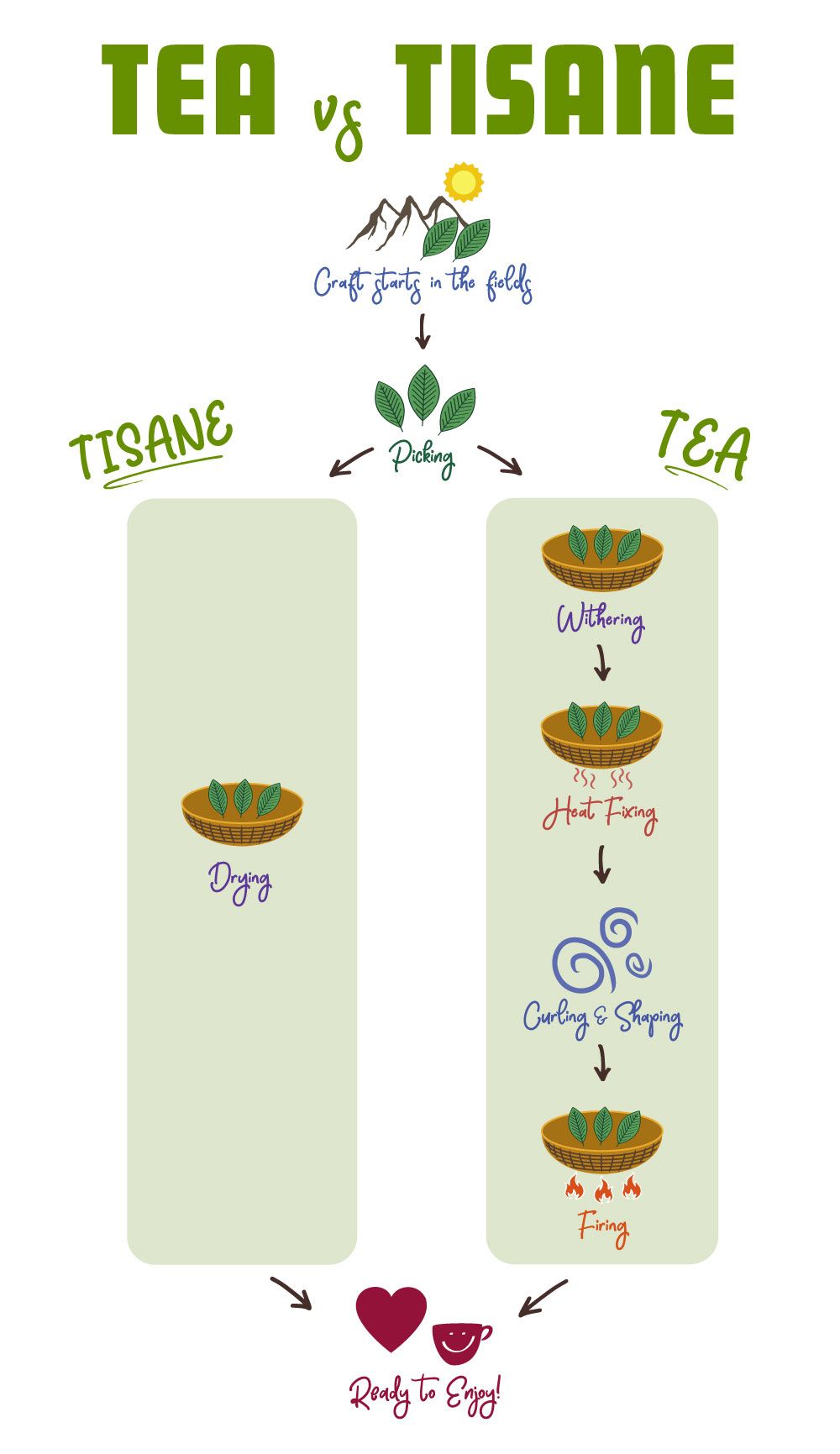

• Tea is finished with a complex heat-fixing process, while a tisane is dried without heat-fixing

What is Herbal Tea?

An easy herbal tea definition is any dried plant prepared for infusion that is not Camellia sinensis. This name might be confusing - many think of “herbs” as culinary plants (like rosemary and sage), but herbal tea can be any plant you steep.

Tisane and herbal tea can be used interchangeably; tisane’s meaning is the same as herbal tea, but without the confusion of herbs vs spices.

Is tea an herb, too? Yes! But generally, craft and species separates tea from other herbs.

How Is Herbal Tea Made?

Herbal tea may be brewed just like tea, but when comparing herbal tea vs tea, there is a clear difference in how each is produced.

Herbal tisanes are picked and simply dried - either in the sun, in circulating air, or with low heat. In contrast, tea requires heat-fixing to lock in flavor, along with deliberate shaping and other processes designed to bring out flavor or lock in freshness.

The culture of tea grew out of the way craft was applied to its finishing and preparation. Indeed, the word “tea” in English and 茶 (chá) in Chinese are separate and distinct from tisane or 荼 (tú) in order reflect this meticulous craft.

-

• Both tea and herbal tisanes are brewed using the same techniques

-

• A tisane is simply dried, while tea requires intensive multi-step finishing

-

• The heat-fixing step that locks in tea’s flavor truly separates it from a simple drying process.

Tisane Health Benefits

Dried herbs brewed in hot water are some of the oldest medicines in human history.

Common tisanes like ginger, mint, and elderberry are generally recognized as safe, but make sure to check for contraindications specific to medicines. As always, consult with a trusted family doctor for medical advice.

-

• Drinking any tisane instead of a sugary drink or alcoholic drink is a clear win with documented health benefits for the whole body.

-

• A habit of drinking more liquid helps prevent headaches caused by mild dehydration and promotes better overall health

-

• The relaxation and stress relief that the ritual of sipping a hot herbal tea brings can counteract hypertension and other stress-related issues

taking time to relax with herbal tea

Does Herbal Tea Have Caffeine?

Are all herbal teas caffeine free? Not always, but most herbal teas are caffeine-free. In fact, reducing caffeine is one of the main reasons people turn to herbal teas, making them great for drinking at night.

Tisanes can be a much better choice than decaffeinated tea, which undergoes harsh processing and never reaches zero caffeine.

cacao, yaopon, guayusa and more contain caffeine

Be sure to check carefully if you need to avoid caffeine. A few herbals are natural stimulants, such as:

-

• Chocolate and cola

-

• Yerba mate and yaupon

-

• Guarana and Guayusa

Exceptions to the Rule

The definition of tisane vs tea is more contentious than it might seem. The word “tea” is about the weight of the culture and history behind the beverage, and the desire by some to draw a line in the sand. After all, tea is named separately from other herbals or tisanes precisely because of the craft involved in making and brewing it.

This distinction between herbal tea vs black tea becomes harder when you consider close tea relatives like Camellia crassicolumna in Qianjiazhai. The leaves of this caffeine-free plant are withered in the sun like tea, then pile-oxidized and wok-finished using black tea craft. Crassicolumna plants are an ancestral relative of tea, and its leaves are being finished with tea craft.

Or consider the He Family in Laoshan, pioneering tea techniques with foraged herbs like Goji Leaf and Gan Zao Ye.

With the same care and craft they use for their traditional teas, the He Family is heat fixing the fresh herbal leaves, withering them, curling them, and tumbling them like traditional green tea.

Over hundreds of years, people realized that tea was sweeter and more delicious with processing than it was fresh or simply dried. Now, this insight is being applied to other herbs. The results go beyond traditional herbal teas and cross into “real” tea.

Tea craft applied to non-tea herbs incentivizes the experimental techniques and empowers farmer projects by sidestepping the downward pressure of commodity markets with a craft product. That’s why the cultural weight of the word tea should be awarded based not on plant species, but on craft.

Experience High Quality Herbal Tea Crafted With Care

The distinction between tea and tisane is all about craft.

Traditionally, the Camellia sinensis plant was the only herb that got extensive heat-fixing, withering and shaping to lock in the flavor of the place. The culture around tea encourages meticulous finishing craft and mindful brewing. Yet, innovation is coming, and the gatekeeping of language isn’t stopping farmers like the Dongsa Cooperative in Qianjiazhai or the He Family in Laoshan from arguing that herbs hand-finished with painstaking tea craft deserve to be called tea, too!

See what the excitement is about with herbal teas from traditional tea farmers >>

Join our CSA-style tea of the Month Club to get to know the work of small family farmers >>

Kickstart your tea discovery with a free tea sampler!

Just sign up for our daily deal newsletter and we'll send you a special coupon

This article has been updated from an older post, originally published July 11th, 2019.

Thousands of years ago, there was not a word for “tea.”

When Camellia sinensis (tea) was first used in Chinese medicine, it was referred to as tu (荼), the same word used to generally describe any medicinal plant. Only when craft and ceremony started to surround tea in the Han dynasty did the plant get its own specific character (茶)cha. In recognition of its cultural importance, there was a deliberate attempt in the language to elevate tea. At this point, diverging craft and tradition separated teas as unique and distinct from other herbs that would have been dried or eaten directly.

Today, the weight of that distinction is a line in the sand between the simpler herbal teas – picked, dried and steeped out in large pots – and the “real” tea, Camellia sinensis, that requires meticulous finishing and craft at every stage and has inspired an entire aesthetic culture of teaware, ceremony and tasting.

For many of us, this line is clear. It seems easy enough to say that “real” tea is Camellia sinensis while herbal tisanes encompass everything else.

Here’s the problem with that distinction.

Here’s the problem with that distinction.

By putting all the cultural value that the word “tea” inspires behind one species of plant, we are missing the opportunity to appreciate the craft, devotion and subtle taste experience that can bring out beauty in other plants.

I’d like to submit to the tea community at large that the cultural weight of the word tea should be awarded based not on plant species, but on craft. After all, it was the craft of tea that originally made it necessary to distinguish 茶 and 荼.

It is rare indeed to find those herbs and flowers whose craftsmanship and finishing are as meticulous and intensive as Camellia sinensis. Most herbal teas are made with ingredients that are picked and then air dried without heat-fixing, curling, roasting, fluffing, aging or any of the other processes that make tea so beautiful.

Yet, there are exceptions to the rule, exceptions that are so stunning that they make me completely rethink the way I use the word tea. These exceptions are coming from two of our closest partners in China, the He Family in Laoshan, and the Dongsa Cooperative in Qianjiazhai.

The He Family lives at the foot of the Laoshan mountains, a protected parkland full of wild herbs. For years, He Qingqing’s mother has been a devoted herbalist wild-foraging medicinal herbs like Goji Leaf, Jujube Leaf, Mulberry Leaf, Huai Flowers, and even Dandelion Leaf.

She used to dry these herbs to brew as fortifying tonics for those long days in the workshop and in the fields picking and finishing her family’s stunning teas. Yet, in the last few years, the He Family has been taking these much further, experimenting in their workshop by taking the fresh leaves and flowers and giving them the same treatment as their teas.

All of these “non-tea” leaves are spread in bamboo baskets to wither, quickly heat-fixed to lock in their flavor and efficacy, curled to bring out deeper complexity (breaking down plant cell walls and creating a light oxidation effect), and finally, dried over controlled heat in woks and tumblers to bring moisture down to about 3% as quickly as possible. This last step prevents hydrolysis reactions from changing the flavor and keeps the finished leaves food safe and shelf stable. The heat and finishing that the He Family bring to their herbs locks in a different portrait of these herbs’ natural flavors, bringing out their sweetness, eliminating bitterness, and coaxing out their hidden complexities.

Over hundreds of years, people realized that tea was sweeter and more delicious with processing than it was fresh or simply dried. Now, this insight being applied to other herbs by people like the He Family. The results are what I would argue go beyond our understanding of herbal teas and instead cross over into what should rightfully be called “real” tea.

The Dongsa Cooperative in Qianjiazhai is so remote that a generation ago even their Camellia sinensis var. assamica was too undervalued to be worth picking any more than staple food crops. In only the last few decades, the demand for their wild-forages ancient tea tree pu’er has skyrocketed as the domestic market realizes what a rare opportunity teas from Qianjiazhai really are. This means that the craft of tea is still new, and still being taught and shared with new craftspeople across the area by community leaders like Master Zhou.

This living memory of perhaps the last region on earth that hadn’t yet truly drawn a value difference between cha and tu means that people here are much more open-minded about finishing techniques and more respectful of all the plants that they can forage.

This open-mindedness has led to an “herbal” tea awakening in the area, with distant caffeine-free tea relatives like Camellia crassicolumna being wild-foraged, withered aged, and pressed into cakes just like sheng pu’er picked from Camellia assamica trees. The result is that over the last few years, demand for wild crassicolumna has begun to exceed demand for “real” tea.

Indeed, with its long aftertaste and sweet, rich texture, Crassiclumna is just as nuanced and complex as “real” tea. The devotion that Master Zhou, the Li Family and the whole cooperative put into foraging for this plant and carefully finishing it is at least equal to their “traditional tea.” So if pu’er (made from Camellia sinensis var. assamica) can be called tea, why not its cousin, Camellia crassicolumna?

The He Family and the Dongsa Cooperatives’ wild-foraged experiments are limited and highly seasonal, but they might be new a blueprint for herb farmers across the world.

Why should any small farmer going through the labor of tending their fields and the craft of balancing their agriculture have to have their product treated like an auction commodity, no different from the next field over? Why should mint farmers or tulsi farmers be denied the chance to offer something that goes beyond the commodity market and in doing so, creates a more economically sustainable model?

The introduction of finishing craft is a path forward towards this vision, a way for small farmers to tap into the culture of tea and offer the world something new and beautiful. We look forward to seeing what the future brings!

How To

How To Myths & Legends

Myths & Legends Travelogue

Travelogue Tasting Journal

Tasting Journal Talking Shop

Talking Shop Tea 101

Tea 101 Watch

Watch Teaware

Teaware News

News

Here’s the problem with that distinction.

Here’s the problem with that distinction.

Leave a Reply

David: I so appreciate this article and fascinated by it, personally. I have done my own diy vsmall batch experimentations with "fermenting" different herbs. I'd like to try and process yaupon